by Catriona Miller and Adèle Brailly | Summersemester 2017 | Freie Universität Berlin

______________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

“The World Press Photo Foundation works to develop and promote quality visual journalism because people deserve to see their world freely.”

This is how the World Press Photo Foundation, a non-profit organization, introduces the exhibition of the prized photographs from its annual World Press Photo contest[1]. This contest is only open to professional photographers and has an international reputation regarding photojournalism. This year, the images were selected from 80,408 images, made by 5,034 photographers from 126 different countries[2]. The exhibition is then seen by more than 4 million people worldwide each year and the prized photographs benefit from widespread media exposure. The Foundation contributes therefore to the establishment of international standards in the field of photojournalism.

The purpose of the contest is to reward photographers who inform about global news, by showing the world objectively – as it really is – through photographs. This is important because people deserve to see their world “freely”. The notion of truth seems to be at the very centre of contest. The photographers show the truth, and the photographers and judges are objective.

Yet, we all appreciate the subjectivity of photography as an art form, and the subjectivity of media bias. Why is it that when it comes to photojournalism, such scepticism is often lost? The photograph is not a fragment of reality but has a narrative dimension. It is constructs a version of reality. Photography, as any other discourse, is constructed through a framing process. In this case, literally. Photojournalism is as prone to bias and reproducing postcolonial discourse, if not more so, than any other medium. Furthermore, we believe that the claim to objectivity actually worsens the effect of such biases, as it shuts down any attempt at critique and discourages people to think critically about what they see.

Besides this alleged objectivity, it is assumed that people deserve to see these images. What does “deserve” in this context mean? Do the photographed people deserve to be shown? With what right are “people” allowed to see the life (or death) of others?

Hence, the aim of our project is to critique the notion of objectivity in the World Press Photo contest from a post-colonial perspective. We state that this contest contributes to an othering process of the alleged under-developed countries through miserabilist photographs. This kind of images serve to substantiate the two dimensional concept of a superior, conflict-free western world in relation to the consistently poor and helpless Other. By “western world” we mean an ensemble of countries including Europe, as well as many countries of European colonial origin with substantial European populations in the Americas and Oceania. This expression refers to the so- called “developed countries”. The absence of violent images from the western countries also helps to reaffirm notions of a more civilized and peaceful society. This is discussed in Part I. Part 2 explores the impact of these representations on the photographed subject as well as the audience. The photographed people often seem to be used by the photographers to deliver a specific message. There seem to be no limits regarding the dignity or privacy of subjects and the degree of violence shown. Does the aim of informing people informed about the news justify disregarding the consent or dignity of the photographed people? Do this kind of photographs encourage empathy on the part of the viewers and does this lead to positive changes in behaviour?

-

Dedication to truth? The construction of a power discourse

One of the first things you notice upon visiting World Press Photo exhibition is the amount of pain and suffering on display. Photographs cover crises from the spread of the Zika virus to the plight of refugees, from the struggles of everyday life in the slums of Brazil to outright war in Iraq, bombing in Syria and the brutal crackdown on drugs in Philippines. These are only a few of the harrowing news stories in the 2017 collection. However, what struck us next was an uncomfortable realization: there only seemed to be these kinds of disasters in non-western countries. The exhibition summed up an entire year of world news and the result seemed to suggest that whilst the West has it all pretty much worked out, everywhere else is in chaos. We know that this is not the case, so why is the exhibition set up this way? Even if the photographs are “true” individually, they only tell part of the story. To pinpoint where the subjective element comes into play is not immediately obvious, since it requires looking beyond the individual photographs to the meaning created from the selection and organisation of these photographs. This is a key stage at which it becomes possible to construct a particular version of the “truth” displayed in the World Press Organisation. However, even in the composition of individual photographs there are plenty of choices to be made which will affect the way we see the world. Here we attempt to demonstrate this through analysing the different representations of “western” and “non-western” countries.

-

A) Representation of non-western countries

Before we go any further, it is important to acknowledge the problems of the term “non-western”. This term defines most of the world in relation to the West, which is assumed as a default. Thus, it can be seen as feeding into the othering process which we are aiming to critique. However, working within the limitations of the English language, it is difficult to find an appropriate catch- all term for this concept. Furthermore, it is used to describe a power dynamic where western, white people are privileged at the expense of many other groups. Therefore, in this context we believe it can make sense to use this term when it is not possible to be more specific about the regions of the world we are talking about.

A recurring theme in colonial discourse is the construction of black, Asian or Latin American people as the “other” in relation to the Caucasian subject. This often leads to dehumanization, where black, minority or ethnic people are seen as less human and not worthy of the same respect as white people, often the first step in justifying prejudice and discrimination. Some photographs in the exhibition seemed insensitive to this issue. For example, this photo of refugees of the coast of Libya:

From the series: Mediterranean Migration, Spot news, third prize stories, Mathieu Willocks (UK)

The most striking thing about this picture at first is the unusual angle the photographer has chosen. The angle forces us to look down at the men in the boat, immediately setting up a power relationship between viewer and subject. Across different creative mediums, vertical hierarchies have long been used to represent real power dynamics. In films for example, it is well known that an angle looking up at characters from below makes them appear large, powerful and in control whereas looking down on people makes them come across as small, vulnerable and powerless. Of course, it is true that refugees are in a vulnerable position, but in a context of hostile, anti- immigration sentiment, there are ways of presenting them in a much more relatable and humanizing way. In this photograph, the separation between viewer and subject is made clear on a literal and metaphorical level. The photographer, Paris-born Mathieu Willcocks, and by extension we as viewers, are not engaging with refugees but merely looking from the outside in. Despite being in the same physical space as the refugees, the Willcocks is clearly not in the same boat, as the rather apt saying goes. In fact, in an interview with Lens Magazine, he admits that it is in a “privileged position”[3] there and he wanted to stay as long as possible. However this is not in relation to his photographed subjects, but in comparison to his fellow photographers who would be envious of shooting in such a difficult location to access. This shows how the photographer is thinking not only of delivering news but also of his own individual gains from the situation. This may underlie other creative choices, such as the aesthetically pleasing bright blue border which frames the picture. Creating artistic photographs in situations where subjects are suffering challenges not only the objectivity but also the ethics of photojournalism. It demonstrates a lack of sensitivity and true empathy for photographed subjects, as they are exploited for individual gain and pleasure of photographers and the western press.

The frequent blurring of the lines between photojournalism and art is another theme seen throughout this year’s prize-winning photos. In no project is this quite as apparent as Daniel Berehulak’s 1st prize photo series documenting the crackdown on drug use in the Philippines.

From the series: They are slaughtering us like animals, General news, first prize stories, Philippines, Daniel Berehulak (Australia)

The photo series plays with colour and light, with each photo fitting into the colour scheme of glowing blues, reds and purples. The result is visually stunning, with pictures such as the one

above making alleyways look almost pretty in the warm reflected light. It is only upon a second glance that one notices the corpse in the corner. It feels almost secondary; it is not the immediate focus of the photograph. Creating such stylistic and aesthetic photos does not seem appropriate or respectful to report on such tragedies. This highlights the entitlement felt by Australian Berehulak, the New York Times and the World Press Photo Foundation to use these people’s stories for their own gain- whether it is as a subject for creative expression, a catching front page or an impressive example of photographic technique. There are certainly other ways in which these people’s stories could have been told.

However, other examples from the World Press Photo Contest show that there are other and better ways to share tragic events with the rest of the world. Notably, these tend to be the relatively rare cases where the photographer is actually from the region they are photographing, and people are telling their own stories. As one would expect, these photos tend to have a more straightforward and humanising approach. They focus more on events and individual experience and less on the aesthetic. One example of this is Syrian-born Ameer Alhalbi’s series of photographs documenting the horrors of the humanitarian crisis following bombing in Aleppo.

Series Rescued from the rubble, Spot news, second prize stories, Syria, Ameer Alhalbi (Syria)

These pictures are not artistic. Rather, they attempt to show life as accurately and realistically as possible. We are forced to confront the full reality of the situation, with no artistic distractions or subtle angles. We can imagine being there, as the photos put us amongst the photographed subjects, in contrast to the distance maintained in Willcocks and Berehulak’s work. Furthermore, it focuses on individuals rather than photographing a mass of people, like so many of the depictions of homogenous groups of refugees. This is a humanizing portrayal of people and their stories.

Another example is the Hossein Fatemi’s second-prize story, “An Iranian Journey”.

Series An Iranian journey, Long-term projects, second prize stories, Iran, Hossein Fatemi (Iran)

In this collection, Fatemi shows a truly diverse collection of photos, illustrating the complexity of contemporary Iranian society. Admittedly, this is a long-term project so it will be more in-depth than other entries in different categories. However, the fact that Fatemi is sharing his own culture allows him to share more intimate and everyday moments. He is able to offer a perspective and truth of life in Iran that an outsider could not. Taking away the mediating gaze of western photographers undoubtable helps when attempting not to reproduce colonial discourse and ways or thinking.

Finally, it is interesting to broaden our focus and reflect once again on the emphasis placed on the representation of “non-western” countries in such an exhibition. This selection allows the west to become largely invisible, which is actually placing it in a position of power as the assumed observer, instead of the subject or scrutiny. The preference for “explosive” and violent images as examples of quality photojournalism also biases the selection of photos towards conflicts and wars in other parts of the country, neglecting the many structural and insidious social crises currently facing the West. Additionally, it simplifies a narrative where Western countries are often heavily involved in conflicts on foreign soil, allowing them to disappear by focusing exclusively on sensationalist consequences rather than the complex build up and context. This feeds into the “saviour complex” where westerners feel they need to help other countries escape their troubles,

ignorant of the West’s previous disruptive interventions. This goes beyond the World Press Photo Foundation, as a challenge to the field of photojournalism in general.

-

B) Representation of the West

The lack of representation of conflict and physical violence within the western world indicates it more civilized and peaceful in comparison to other countries. This is a stark contrast to the numerous miserabilist images taken in the Middle East, Africa and “developing countries” such as Latin America. This may lead the viewers to believe that the western countries are peaceful and developed countries, without any conflicts, violence or social issues. Only 9 in 45 photographic works were taken in occidental countries. And in those 9 photographic works, 5 belong to the category “sport”. Are the sport activities really the main concerns of the western countries? Is there nothing else to talk about?

An example of this is the photographs showing Muddy York Rugby Football Club, referred to as “the first gay-friendly rugby team” in Toronto, Canada. The caption explains that this was set up to resist the idea that gay men were not suitable for a masculine sport like rugby, and to counter the stereotypes surrounding gay athletes. These images present a narrative emphasizing social progress in Canada and depicting it as gay-friendly country.

From the series: Boys Will Be Boys, Sports, first prize stories, Canada, Giovanni Capriotti (Italy)

This is a positive news story which presents the Canadian society as capable of reflexivity, and dealing with modern issues. This builds a contrast with the figure of the supposedly oppressed Muslim woman and more patriarchal social structures in the Middle East.

The few images dealing with conflicts in the West do not show any kind of physical violence. They are neither shocking nor explosive, but aesthetic. For instance, there is a set of photographs which depict the opposition of the standing Rock Sioux tribe against the construction of an oil pipeline in North Dakota. Many of the pacifist demonstrators were injured by the police forces[4]. However, this repression is not shown.

From the series: Standing Rock, Contemporary Issues, first prize stories, USA, Amber Bracken (Canada)

From the series: Standing Rock, Contemporary Issues, first prize stories, USA, Amber Bracken (Canada)

We see the opposing sides only separately, before and after the clash. The photographer has left out any violent confrontations in-between. This only presents a part of the whole truth. Each individual image may claim some level of truth, however the real story we take away is hidden between images: in the progression, selection and juxtaposition of pictures used to construct a story. These photographs depict a sanitized version of events, painting a picture of a diplomatic US police force.

The absence of shocking or violent images from the western countries should be questioned. Social phenomena which are not shown or seen are consequently non-existent in the collective awareness. Yet the image is nowadays considered as a proof of what is happening in the world. The primacy of visual documents is particularly noticeable concerning police violence. The injured body as a proof and/or the testimony are not sufficient anymore. On the contrary, injuries can be considered as being provoked by a violent behaviour. The victims of such acts need to provide images or videos to be believed: These only are irrefutable evidences. The image is thus considered as a fragment of reality: it is “true” because it is an image. It has an absolute legitimacy. But the very essence of the photograph is problematic: the difference between the signifier and the signified disappears. In other words, people do not immediately perceive the difference between what the photographer wants to show and what is shown. The intent of the photographer is erased by the immediate content of the image. However, the photograph is the product of a construction, a framing process.

The images, as any other kind of discourses, contribute to construct social reality. The absence of photographs depicting conflicts in the western world is the result of a normative judgement. Through the judging process of the World Press Photo Contest, the jurors decide secretly which photographs deserve to be seen and which do not. The deliberations are confidential: “All proceedings and deliberations of each jury are conducted in confidence. (…) This means jurors cannot discuss any aspect of the entries, debates or decisions, both during the process and after the announcement of the results, with anyone other than a fellow juror.”[5] We do not know the selection criteria, and the number of photographs from the western world they received. The website only mentions that “the criteria for judging entries is a combination of news values, journalistic standards, and the photographer’s creativity and visual skills.”[6] The jurors are thus free to set their own standards. It is yet obvious that one of the main criteria is the emotion generated, that is, the dramatization effect. Referring to the winning photograph, a juror said: “We felt that the picture of the year was an explosive image that really spoke to the hatred of our times”. It is “a definition of what the world press photo of the year is and means.” The aim is thus to make people emotionally react, in other words to shock the viewers. But do people need to be shocked?

It is interesting to consider what “shocking” actually means. What are the limit of what is tolerable and acceptable? How -and by whom- is this limit defined? In other words, what kind of violence deserves to be denounced? “Violence” is a normative notion. The way people define what is violent varies, often depending on their social background. In the same way, the jurors of the World Press Photo Contest define the limit of what is truly acceptable and deserves to be shown. In this way, they contribute to the legitimizing of a normative colonial judgement through their very definition of what is violent. Photographs which depict war situations, terrorist attacks or other murderous events are exhibited. These are “barbaric” acts, which take place in under- developed or developing countries. But on the other side, the developed one, there are no photographs of such social problems as police violence, humanitarian disasters (an example being the refugee camp in Calais, France), harassment against the LGBT*Q community, domestic violence, catastrophic prison conditions etc. Social problems do exist in the western world as well, but are not as publicized as those in different countries. Discussion about the systemic violence in the western world is silenced on a global scale. The World Press Photo Contest only delivers one truth: its own truth. This can be considered as a dogmatic worldview, reproducing the colonial stereotypes.

-

Can the photographed subaltern speak?

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s seminal 1983 essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?”[7] explored the challenges of oppressed people to communicate their experiences and be heard and understood by their oppressors. She specifically criticized the attempts of western intellectuals to “speak for” the subaltern condition, as taking control of the subaltern’s narrative merely reproduces colonial power structures. Photojournalism so often takes on this dynamic of privileged photographers taking on the task of sharing the plight of distant, misfortunate others, predominantly in so-called “developing countries”. Therefore, Spivak’s question seems highly relevant. Can the photographed subaltern truly speak? Questions surrounding consent, dignity and empathy are important to consider when assessing the relationship between the observer and the photographed subject. Firstly, we explore the role of the photographed subject in terms of ethics and consent. Leading on from this, we look at the impact of photojournalism on its intended audience and whether it has a meaningful effect through inspiring feelings of empathy.

-

A) A question of ethics and consent

The expression mentioned in the introduction of the exhibition: “people deserve to see our world freely” is to be questioned from an ethical perspective. Indeed, who are the people who have such a right? What are they allowed to see? What is the limit of what is acceptable to show regarding the dignity of the photographed people, if any? It appears that the consent of the photographed people is not a criterion for the World Press Photo Contest. To learn more about the place of the photographed people, it can be interesting to study the Code of Ethics mentioned on the website of the foundation[8].

The introduction of the Code of Ethics states: “Entrants to the World Press Photo contest must ensure their pictures provide an accurate and fair representation of the scene they witnessed so the audience is not misled.” The veracity of the photographs is particularly underlined. The photographers have the duty to show the world as it is, without altering their images. Otherwise it would be considered as a manipulation. In other words, as a lie. The Code of Ethics mentions that the photographers must be aware of the influence their presence can exert of a scene they photograph; must not alter the scene they photograph; must provide accurate captions etc. The entire process through which the pictures are made, from the shooting to the editing, must be “transparent” and “accurate”. Again, it is assumed that the photographers show the world objectively.

The speech by the royal patron of the foundation, HRH Prince Constantijn of the Netherlands, at the 2015 Awards Ceremony, illustrates this obsession for truth and transparency: “Good journalism strives to uncover the truth, independent from which angle the story is told.”[9] He means that all is matter of desire to tell a “truthful story”, independently from the social background of the photographers. “This means that alteration of an image for aesthetic reasons or for getting the message across more forcefully is off limits. It is wrong, as it is the equivalent to lying.” Prince Constantijn draws a parallel between the “daily imagery” and “information deluge”, and photojournalism, which is presented as following a noble activity.

In the Code of Ethics, as well as in the speeches of the foundation’s president, no mentions of the photographed people are made. They seem to be considered as photographic objects more than photographed subjects. Their consent to be photographed and seen by “more than 4 million people worldwide each year” is not taken into account. Do the photographed people deserve to be seen while their dignity is compromised? Does the desire to show the truth under the name of freedom of expression justify ignoring the voice of the photographed people? To answer the question – Can the subaltern speak? – in the context of the World Press Photo Contest, it is interesting to look at the conditions for the organization and conduct of the contest.

It is interesting to note that the majority of the jury members come from western countries, mainly from USA and UK[10]. Only 5 in 25 jurors do not come from occidental countries (That is, Palestine, Ethiopia, South-Africa, Brasilia and Japan). Stuart Franklin, chair of the contest, is a national of the United Kingdom. As mentioned above, the deliberations which take place during the judging process are entirely secret. It is thus impossible to know what exactly the selection criteria are. But it is intriguing to note that the majority of the selected photographs were not taken in the western countries.

We sent an e-mail to Director of Communications of the World Press Photo Foundation, David Campbell, to learn more about the question of consent. According to him, the jurors assume that the contest entrants are professional photographers, who are already aware of the ethical issue in the field of photojournalism: “There are a number of important issues beyond our code, including the question of consent.” With regards to the assertion that people “deserve to see the world freely”, he explains that the foundation is committed to freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of expression. The foundation is aware of the risk of exploiting tragedy while reporting on “difficult issues”, which is a subject of “constant debate”. But the value of freedom seems more important than the value of consent and dignity, or rather the photographed subject’s freedom to control their own narrative: “if consent was to be required for all news photo to be taken, it is quite likely there would be serious restrictions on what could be reported and when, reducing vital information on some of the world’s most important issues.” But how are a “vital information” and an “important issue” defined? Do we have more of a right to people’s stories than they do?

The so-called subalterns don not interfere the entire selection process and do not have access to the exhibitions, after the judging process, as illustrated in this map:

Screenshot of the map showing the upcoming exhibitions and events for the year 2017[11]

Although “the exhibition of award-winning photos is shown worldwide in 100 cities and 45 countries, reaching a global audience of 4 million people each year”, the exhibitions are mainly concentrated in Europe and in the western countries. The intentions behind these exhibitions seem to show the inhabitants of the developed countries what is happening elsewhere, to other people. Hence, the photographed people cannot speak. They become photographic objects, representing such tragedies as poverty, war, disease, death, despair etc. They are used by the World Press Photo

Foundation, which doesn’t refer to any kind of given consent. Perhaps such photographs play a cathartic role in the mainstream western consciousness.

In this context, the images of corpses are the ultimate illustration of the absence of given consent. The corpse is used as an artistic object, producing an aestheticized depiction of death, like in the following picture:

From the series: Iraq’s Battle to Reclaim Its Cities, General News, second prize stories, Iraq, Sergey Ponomarev (Russia)

Once again, the line between artistic photography and journalistic photography is blurred. This image shows that the very essence and mission of photojournalism is still to be defined. Given the absence of ethical standards regarding the photographed people’s dignity, the photographers are free to create their own definition of photojournalism. Photographers and editors set their own limits of what is acceptable to show and how it is portrayed. They are able to exploit suffering of the photographed subjects for their individual gain, in fact it could be argued that this is encouraged through the very process of awarding prizes and professional recognition through the World Press Photo Contest.

-

B) A question of empathy

In fact, there are several questions when it comes to empathy in the context of the World Press Photo Contest: What makes a photograph inspire feelings of empathy towards its subjects? Does the World Press Photo Contest reward these types of photos? Finally- does photojournalism affect people enough to actually bring about a positive change in attitudes and behaviour? This is the belief of many photojournalists, as Berehulak stated in a recent interview: “By telling these personal stories, that’s how I’m hoping to connect and make people think about what they’re doing and possibly change how we’re living our lives.”[12]

There is a distinction to be made between an immediate emotional reaction and a feeling of empathy. The former is generated by a shocking (often bloody) image, whereas the latter is connected to social awareness.

Firstly, to feel empathy, we need to be able to relate to somebody else on a human level. Therefore, if a photograph is going to trigger feelings of empathy, it must present people in a humanising, relatable light. Certain categories in the World Press Photo Contest lend themselves to this, such as the “long-term projects” where we really get to know particular communities, or the “people” category which focuses on the stories of individuals. For example, consider this picture of Maha (5) being “comforted by her mother, in Debaga refugee camp in north-eastern Iraq”:

What ISIS left behind, People, first prize singles, Iraq, Magnus Wennman (Sweden)

This is a close-up portrait of Maha. This is conducive to triggering empathy, since we can clearly see her facial expression and better understand how she is feeling. The focus on a child confronts us the human cost of war whilst playing on our protective instincts and increases our desire to reach out and help her. The fact that she takes up the entire photograph places the focus solely on her and her story in this moment. The caption elaborates on her experience, whilst putting it into the broader context of the conflict between Iraqi troops and ISIS. This helps to educate people about news and issues in other parts of the world in a personal, impactful way.

However, there were several occasions when the exhibition displayed photos which did not depict oppressed people in a humanising way. Examples include some from the first section part A, such as Berehulak’s documenting of murders in the Philippines where the focus was often not on the intended subject, or Willcocks’s series on refugees. Both maintained a certain distance between photographer and subject. This particular photo taken by Willcocks illustrates this:

From the series: Mediterranean migration, Spot news, third prize stories, Matthieu Willcocks (UK)

The refugees are photographed as a homogenous group. This lack of individuality is dehumanising and thus makes it more difficult to empathise with their situation, as it feels more abstract and they aren’t shown on an individual human level. Another interesting feature of this photograph is the fact that they are all desperate and dependent on handouts from the men on the boat. As previously mentioned, the anti-immigration sentiment in Europe thrives on the depiction of immigrants as dependent and a burden. Therefore, choosing this particular photograph may be particularly ineffective in inspiring feelings of empathy in western countries.

However, even where photographs come across in a sensitive, empathy-inducing manner, does it ever make a difference? The hope that such photographs will initiate real changes is the justification for foregoing concerns such as privacy and consent discussed in the previous section. Is this just an excuse? In this case, many of the photos in this exhibition would be voyeuristic and sensationalist.

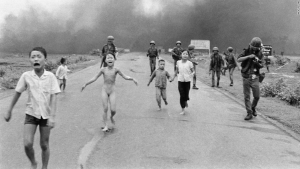

On the one hand, there have been examples of photos which had a significant impact on public opinion. In 1972, Nick Ut’s photograph of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc running naked after being severely burned by a South Vietnamese napalm attack shocked the world. It is widely credited as being a major factor in turning American public opinion against the war, contributing to the decision of the US to end direct military involvement the following year.

The Napalm Girl, Nick Ut, 1972 – Pulitzer Prize for Spot news photography for “The Terror of War”, 1973

However, since then our culture has become more and more image-based, and we are used to seeing “shocking” images such as this one all the time. The amount of graphic imagery in the World Press Photo Contest alone testifies to this. This begs the question: do graphic depictions of human suffering still shock us, or are we getting desensitised to it? Clearly many people in the West are not driven to action even after viewing so many graphic, violent photographs. It feels unlikely that Ut’s photograph would have generated the same effect today as it did in 1972. Although images can invoke a feeling of empathy, research shows that when they are viewed “in a context where solutions to the conflicts seem improbable or out of reach, in most cases, that compassion and empathy stagnates![13].

This leads us to believe that the extreme imagery from non-western parts of the world is sensationalist and thus, by objectifying and exploiting the photographed subjects for commercial gain, colonialist in nature. Furthermore, it could be argued that the fact that such “pornographic violence”[14] is only displayed in non-western countries decreases feelings of empathy and instead intensifies a feeling of otherness and difference. This is because it sends the message that it is our right to view the private lives of oppressed people – as if we own their experiences and can consume them whenever and however we choose. This is a stark contrast to how we are encouraged to relate to occidental people.

An example of this is how we treat victims of terror attacks in the western media. European or American victims are usually reported using personal photos and images from the aftermath blur out the faces of corpses to protect them and preserve their human dignity. However, the publishing of the following photograph of a terror attack in Pakistan is the opposite: graphic and sensationalist, not a thought to protecting their identity or presenting victims in a humanising way.

Pakistan Bomb Blast, Spot News, first prize singles, Pakistan, Jamal Taraqai (Pakistan)

Despite the shocking nature of this image, it is interesting to imagine just how much more shocking it would be had the people in this photo been British commuters on London Bridge. By saying we deserve to “see the world freely”, the World Press Photo Contest seems to assume it operates in a vacuum. Yet the double standard of how black and white people are portrayed shows otherwise. It is dangerous to imply objectivity when in fact, we are all impacted by the enduring effects of colonialism which still impact real people’s lives today.

Conclusion

Overall, it can be seen that there is a difference in how “western” and “non-western” people and countries are presented throughout the World Press Photo Contest. Due to the dehumanisation, othering and disregard for people of colour in certain photographs, we conclude that there are colonial undertones in some of the works in this exhibition. In fact, the whole concept of the exhibition is questionable, as a predominantly white, western audience is presented with the interpretation of predominantly white, western photographers of people’s struggles in different parts of the world. However, we do not advocate an end to photojournalism, or, indeed, the World Press Photo Contest altogether. We believe that good quality photojournalism is important and can be done in a sensitive way. Expanding the Code of Ethics to provide more guidelines on maintaining photographed subjects dignity is necessary to avoid reproducing oppressive, colonial discourses. Furthermore, an emphasis on respectful, humanising approaches to people’s pain and suffering would lessen the danger of sensationalism and instead encourage a sense of empathy in the viewer. This may not only help drive people to action to change things, but also start to replace the divisive “us” and “them” narrative by more of a “we” feeling. One practical suggestion from Midberry’s study on empathy in war photojournalism is to further explore the way “news organizations can capitalize on the emotional and empathic responses evoked by humanizing war photos by offering solutions and hope to their audiences.”[15] Most importantly perhaps, we believe that the World Press Photo Contest exhibition should avoid implying impartiality and instead make people aware of the subjectivity of photojournalism, the difficult nature of navigating oppressive power dynamics and encourage them to think critically about photographs they see instead of accepting them as the truth. There are, indeed, alternative ways to do photojournalism. In the Shootback project[16], for instance, the so-called subalterns are free to tell their own stories: American photographer Lana Wong gave young people in Nairobi’s slums plastic cameras and taught them photography. Hence, the kids could photograph what mattered to them, without any intention to show the pain of the world – that is, without any miserabilistic point of view.

Bibliography

CARON Caroline, “Humaniser le regard. Du photojournalisme humanitaire à l’usage humanitaire de la photographie. ”, Commposite, 2007, p. 1-19.

MIDBERRY Jennifer, Visual frames of war photojournalism, empathy, compassion, and information seeking, Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of philosophy, Temple University, 2016, 187 p.

SPIVAK Gayatri Chakravorty, “Can the subaltern speak?”, in NELSON C., GROSSBERG L., Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, University of Illisnois Press, p. 271 – 313.

‘A conversation with Alfredo Jaar’, Nihilsentimentalgia, URL: https://nihilsentimentalgia.com/2017/06/25/pictures-of-atrocity-and-pornographic-imagery-a- conversation-with-alfredo-jaar/

Website of the World Press Photo Foundation, URL:

https://www.worldpressphoto.org/collection/photo/2017 Website of the Shootback project, URL: http://www.shootbackproject.org/about/

WILLCOCKS Mathieu, “An Interview with Mathieu Willcocks”, interviewed by Anne Pinto- Rodrigues, 2017

______________________________________________________________________________________

[1] The rewarded photographs are available on the website of the World Press Photo Foundation: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/collection/photo/2017

[2] Ibid

[3] Willcocks was interviewed for the May 2017 issue of Lens Magazine URL: http://lensmagazine.net/an-interview- with-mathieu-willcocks/

[4] Twenty-six people were hospitalized and more than 300 injured after the police forces used water cannons, teargas and less-than-lethal weapons on unarmed activists during the night of the 20th of November 2016: “Dakota Access pipeline: 300 protesters injured after police use water cannons”, the guardian, URL: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/21/dakota-access-pipeline-water-cannon-police-standing-rock- protest

[5] “Photo Contest Judging Process“, world press photo, URL: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/activities/photo- contest/judging

[6] Ibid

[7] SPIVAK Gayatri Chakravorty, “Can the subaltern speak?“, in NELSON C., GROSSBERG L., Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, University of Illisnois Press, p. 271 – 313.

[8] “Photo Contest Code of Ethics“, world press photo, URL: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/activities/photo- contest/code-of-ethics

[9] “Speech by HRH Prince Constantijn oft he Netherlands at the 2015 Awards Ceremony“, world press photo, URL: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/news/2015-04-25/speech-hrh-prince-constantijn-netherlands-2015-awards- ceremony

[10] “Photo Contest Jury“, world press photo, URL: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/activities/photo-contest/jury

[11] “Exhibitions & events“, world press photo, URL: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/exhibitions 14

[12] “Daniel Berehulak”, world press photo, URL: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/people/daniel-brehulak

[13] MIDBERRY Jennifer, Visual frames of war photojournalism, empathy, compassion, and information seeking, Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of philosophy, Temple University, 2016, p. 144.

[14] During an interview, the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar explained the similarities between ‘pictures of atrocity’ and ‘pornographic imagery’: “I would attempt to define pornography as the sexual exploitation of any human body for purely commercial purposes. (…) On the other hand, documentary pictures of atrocities are exactly that: the graphic representation, through photography, of violent acts.” In ‘A conversation with Alfredo Jaar’, Nihilsentimentalgia, URL: https://nihilsentimentalgia.com/2017/06/25/pictures-of-atrocity-and-pornographic-imagery-a-conversation-with- alfredo-jaar/

[15] MIDBERRY Jennifer, Visual frames of war photojournalism, empathy, compassion, and information seeking, Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of philosophy, Temple University, 2016, p. 144.

[16] WONG Lana, Shootback : Photos by kids from the Nairobi slums, London, Booth-Clibborn Editions, 1999. Website of the project: URL: http://www.shootbackproject.org/about/

______________________________________________________________________________________